SOAR Method

Successful Leaders Don’t Climb the Corporate Ladder, They SOAR

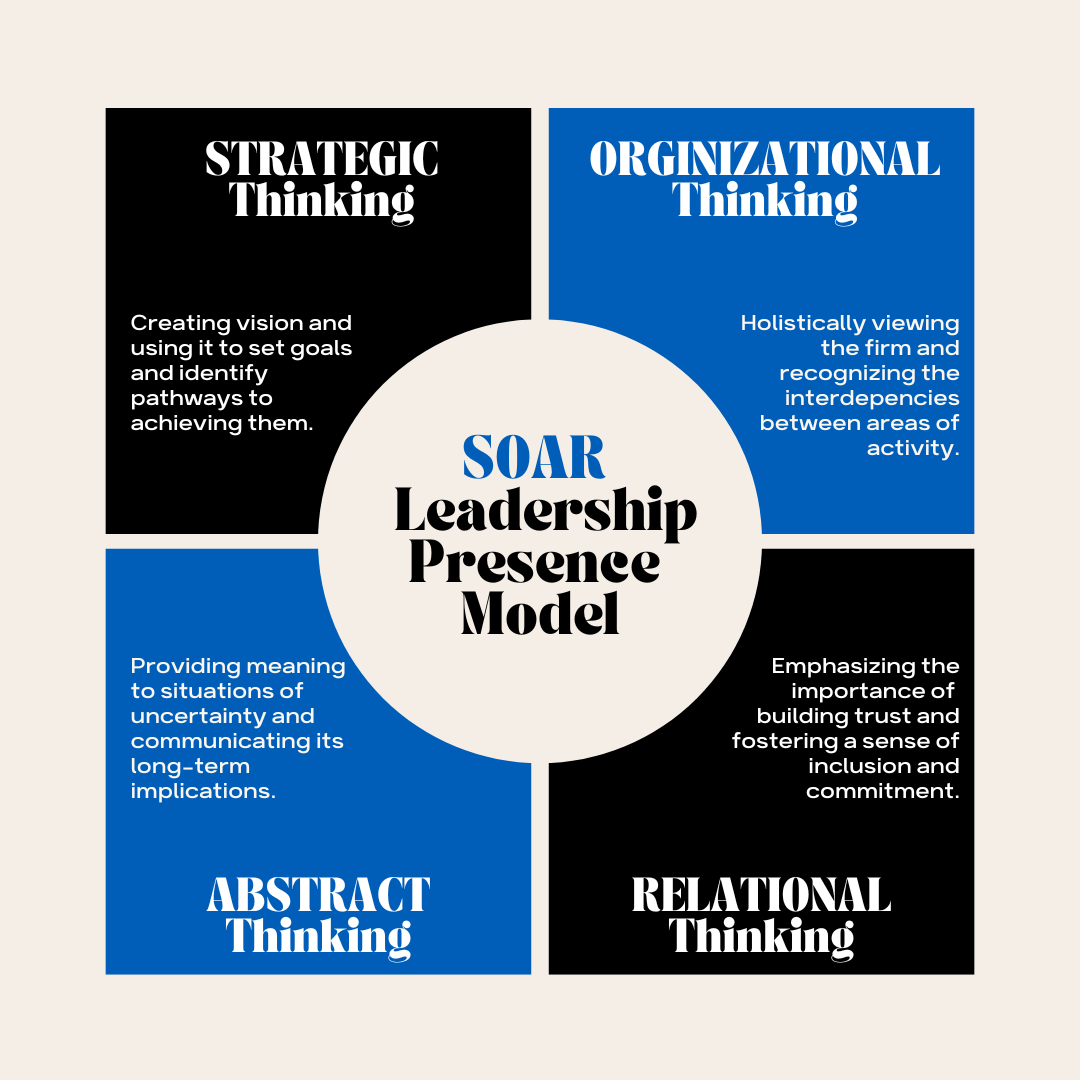

As leaders ascend to higher levels of responsibility within a firm, their roles and the skills required for success evolve significantly. This transition demands a shift from technical and operational expertise to a focus on thinking strategically, organizationally, abstractly and relationally, referred to as the SOAR Leadership Presence Model™ developed by Dr. Eric Boyd at Inntinnean Coaching.

STRATEGICALLY Thinking

Early in their careers, leaders often rely on technical skills and operational expertise. However, as they rise through the ranks, the importance of these skills diminishes, and the need for strategic vision becomes paramount. According to Charan, Drotter, and Noel (2011), leaders must shift their focus from managing tasks to setting a strategic direction for the organization. This involves understanding market trends, foreseeing future challenges, and developing long-term plans that align with the firm's goals.

A study by Dragoni et al. (2014) found that leaders who successfully transition to higher levels exhibit strong strategic thinking skills. They can analyze complex environments, anticipate industry shifts, and create adaptive strategies. This shift from operational to strategic thinking is crucial for leaders to guide their organizations through uncertainty and change.

ORGANIZATIONALLY Thinking

The importance of leaders thinking organizationally rather than functionally is paramount in fostering holistic growth and ensuring the alignment of departmental goals with the overall strategic objectives of the organization. When leaders adopt an organizational perspective, they can better understand the interdependencies between various functions and how decisions in one area can impact the entire organization (Yukl, 2012).

An organizational view facilitates more cohesive and coordinated efforts across departments, enhancing overall efficiency and effectiveness. Additionally, research by Hannah and Eggers (2010) indicates that leaders who think organizationally are better equipped to manage complex, dynamic environments, as they can anticipate and address cross-functional challenges more effectively. By focusing on the organization's broader goals, leaders can foster a more unified culture, drive strategic initiatives more effectively, and ensure that all parts of the organization work towards common objectives, ultimately leading to sustained organizational success (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967).

ABSTRACTLY Thinking

The ability of leaders to think abstractly is crucial for navigating the complexities and uncertainties inherent in today's dynamic business environments. Abstract thinking enables leaders to conceptualize and envision the broader implications of their decisions, allowing them to develop long-term strategies that align with the organization's vision and goals (Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987).

This cognitive skill also facilitates innovative problem-solving by helping leaders see beyond the immediate and obvious solutions to underlying patterns and potential opportunities (Mumford, Zaccaro, Harding, Jacobs, & Fleishman, 2000). Furthermore, abstract thinking enhances a leader's ability to integrate diverse perspectives and knowledge areas, fostering more comprehensive and adaptive decision-making processes (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1993). Leaders who excel in abstract thinking can anticipate future trends, prepare for potential disruptions, and guide their organizations through complex transformations, thereby ensuring sustained success and competitive advantage (Boal & Hooijberg, 2000).

RELATIONALLY Thinking

The importance of leaders thinking relationally rather than transactionally is underscored by the positive impact on employee engagement, motivation, and organizational culture. Relational leadership emphasizes the importance of building strong, trust-based relationships with employees, fostering a sense of belonging and commitment (Uhl-Bien, 2006). In contrast, transactional leadership, which focuses on exchanges and rewards for specific tasks, can lead to short-term compliance but often fails to inspire long-term dedication and innovation (Bass, 1990).

Research by Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995) highlights that relational leaders who invest in high-quality engagement with followers create more productive and satisfied teams. These leaders engage in active listening, provide meaningful feedback, and support their employees' personal and professional growth, which enhances overall team performance and organizational effectiveness (Dulebohn et al., 2012). By prioritizing relational thinking, leaders can cultivate a more collaborative, supportive, and resilient organizational culture, leading to sustained success and employee well-being (Walumbwa et al., 2011).

Conclusion

As leaders ascend to higher levels of responsibility within a firm, their skill sets must evolve to meet the demands of their new roles. By embracing the SOAR Leadership Presence Model™, leaders can navigate the challenges of higher-level leadership and drive their organizations toward sustained success.

References

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1993). Beyond the M-form: Toward a Managerial Theory of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, 14(S2), 23-46.

Bass, B. M. (1990). From Transactional to Transformational Leadership: Learning to Share the Vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18(3), 19-31.

Boal, K. B., & Hooijberg, R. (2000). Strategic Leadership Research: Moving On. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 515-549.

Charan, R., Drotter, S., & Noel, J. (2011). The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership Powered Company. John Wiley & Sons.

DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and Behavioral Theories of Leadership: An Integration and Meta-Analytic Test of Their Relative Validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 7-52.

Dragoni, L., Oh, I. S., Vankatwyk, P., & Tesluk, P. E. (2014). Developing Executive Leaders: The Relative Contribution of Cognitive Ability, Personality, and the Accumulation of Work Experience in Predicting Strategic Thinking Competency. Personnel Psychology, 67(3), 713-760.

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Consequences of Leader-Member Exchange: Integrating the Past With an Eye Toward the Future. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715-1759.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-Based Approach to Leadership: Development of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory of Leadership Over 25 Years: Applying a Multi-Level Multi-Domain Perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219-247.

Javidan, M., Teagarden, M. B., & Bowen, D. (2010). Making It Overseas. Harvard Business Review, 88(4), 109-113.

Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Harding, F. D., Jacobs, T. O., & Fleishman, E. A. (2000). Leadership Skills for a Changing World: Solving Complex Social Problems. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(1), 11-35.

Hannah, S. T., & Eggers, J. T. (2010). Leadership in Action: Developing Leaders through an Organizationally Integrated Approach. Journal of Management Development, 29(5), 444-456.

Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Differentiation and Integration in Complex Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(1), 1-47.

Yukl, G. (2012). Leadership in Organizations (8th ed.). Pearson.

Kuhnert, K. W., & Lewis, P. (1987). Transactional and Transformational Leadership: A Constructive/Developmental Analysis. Academy of Management Review, 12(4), 648-657.

Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Harding, F. D., Jacobs, T. O., & Fleishman, E. A. (2000). Leadership Skills for a Changing World: Solving Complex Social Problems. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(1), 11-35.

Uhl-Bien, M. (2006). Relational Leadership Theory: Exploring the Social Processes of Leadership and Organizing. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 654-676.

Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Oke, A. (2011). Servant Leadership, Procedural Justice Climate, Service Climate, Employee Attitudes, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Cross-Level Investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(3), 517-529.